Scientific Sightseeing Tour of Glasgow

These past few days, I have been reviewing my notes for the tour I have prepared of Glasgow’s sites of scientific interest. Glasgow, the city where I currently live, has been the setting for numerous historic scientific events. The route is partially based on the tour organised by The Friends of Glasgow West during the West End Festival in 2015. It lasts approximately an hour and a half and covers a distance of 3.37 km. You can view the route on this map:

Let's explore the stops and their history one by one:

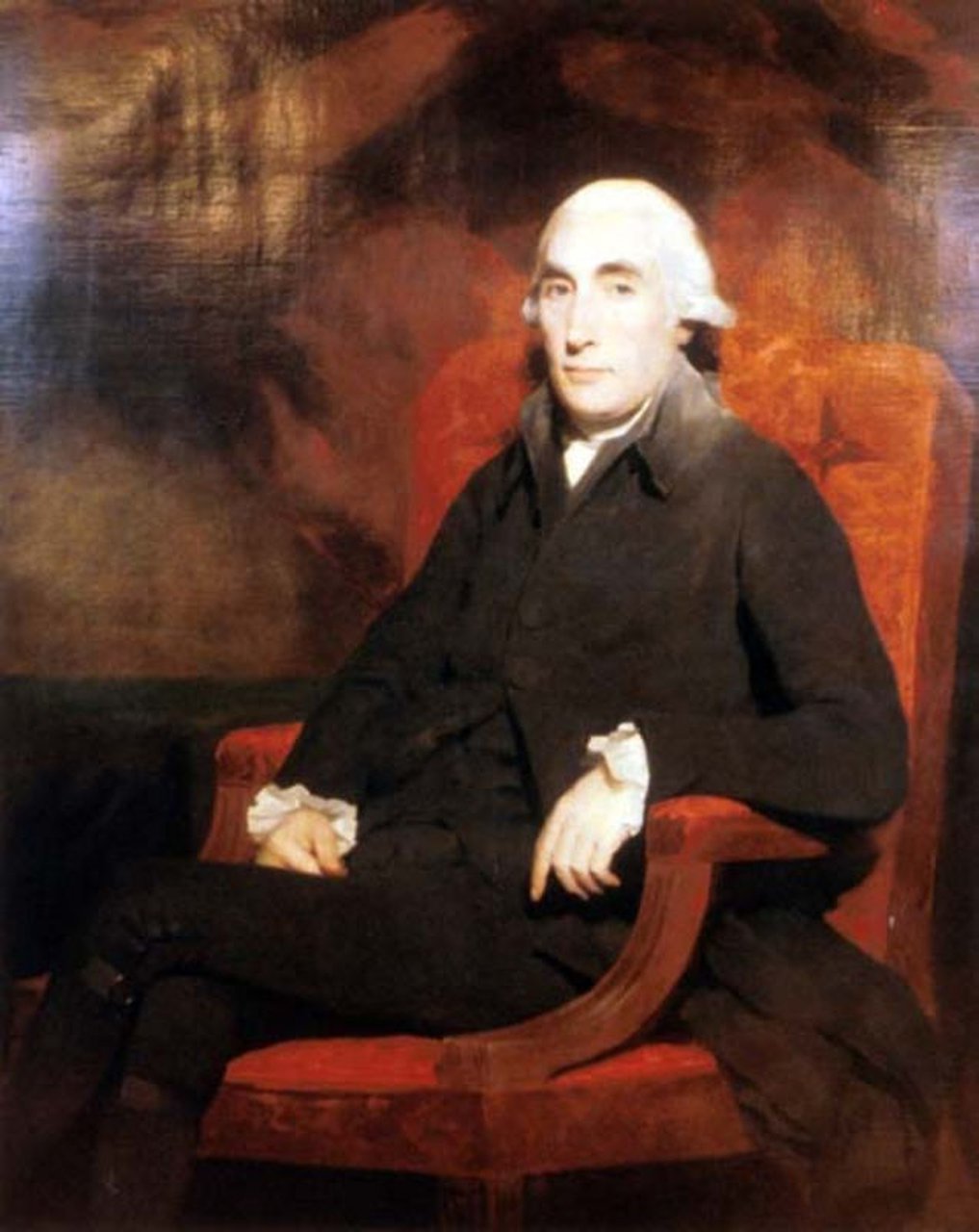

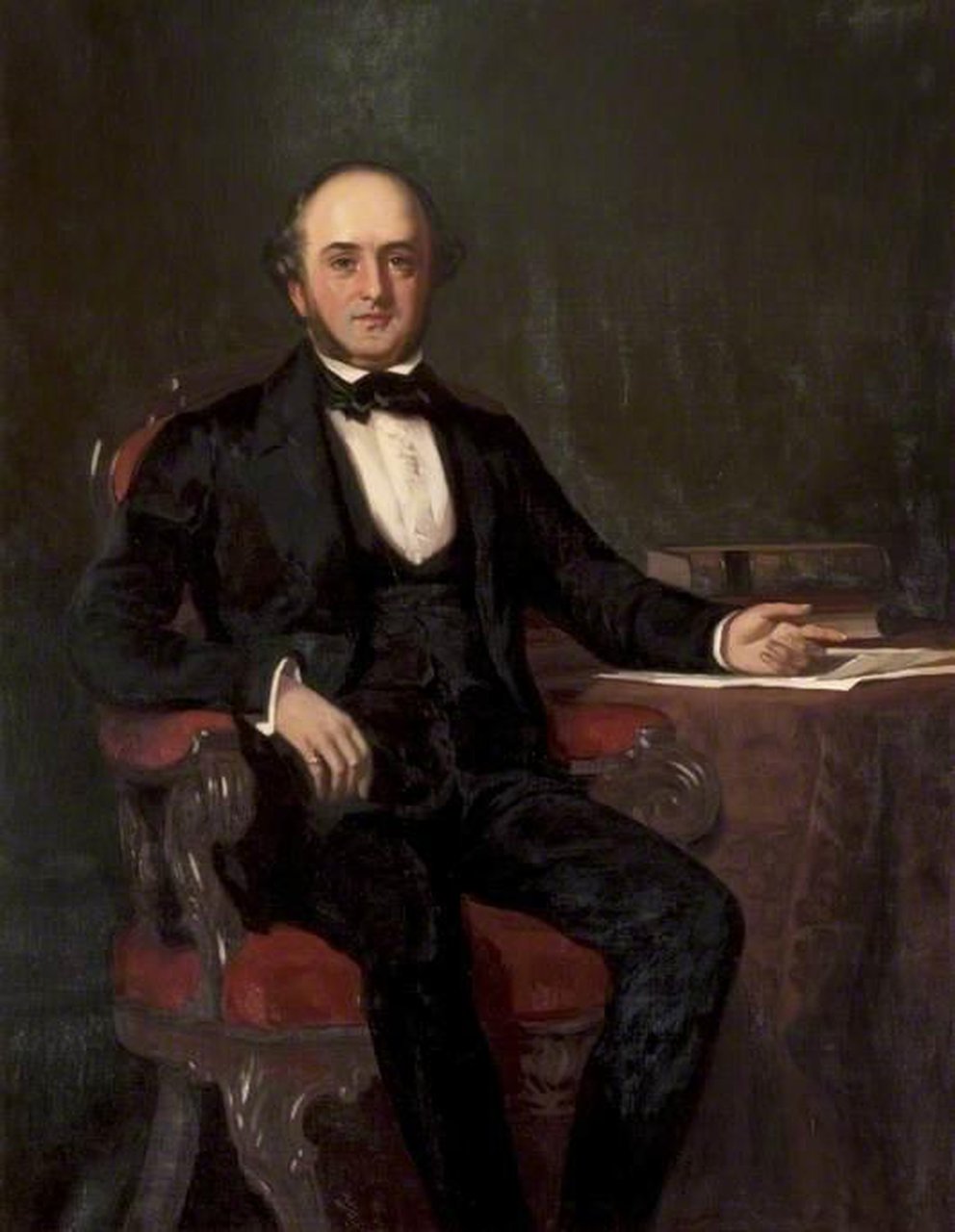

A. Joseph Black Memorial - Joseph Black

University Place

55.872716, -4.293131

This bas-relief was created in 1953 by the Estonian-Scottish sculptor Benno Schotz, commissioned by the University of Glasgow’s governing body to honour the chemist Joseph Black.

Joseph Black was the son of a wine merchant from Ulster and was born in 1728 in Bordeaux. At the time, Rioja wine had not yet reached its full refinement, so he could not be born in Logroño. Black arrived in Glasgow at the age of 16 to study Arts at the University of Glasgow. He spent four years enjoying student life until his father ran out of patience and convinced him to study something more useful: Medicine. At that time, the Professor of Medicine, William Cullen, had just introduced chemistry classes at Glasgow, and he hired Black as his assistant. Through this role, Black learned all the chemical techniques and knowledge of the period and began his thesis on magnesia alba, or according to the 21st-century IUPAC nomenclature, magnesium carbonate—a compound of carbon dioxide, water, and magnesium, as we learned in school.

At that time, it was believed that there were only four elements—earth, water, fire, and air—so conducting research on a compound involved systematically testing reactions with known chemicals such as alcohols, bases, and acids. At the age of 24, Black had a radical (or revolutionary) idea—especially since Lavoisier was only eight years old at the time. He decided to weigh the magnesia alba before and after his experiments. He discovered that it lost weight when heated or treated with acids, realising that this loss was due to the release of a gas—carbon dioxide—which he called "fixed air". He soon recognised that the chemical properties of "fixed air" were different from the only known type of gas at the time—"air"—and he deduced that burning coal, food fermentation, and respiration also produced fixed air.

In 1756, he was appointed professor at the University of Glasgow and began studying the concept of heat with the help of James Watt, who was then the university’s Mathematical Instrument Maker and would later invent the steam engine. Black developed a calorimeter to measure changes in temperature when heat was applied to substances, leading to his discovery of latent heat of fusion. However, precise measurements required cold temperatures, so he eagerly awaited winter.

Joseph Black was an excellent professor, attracting students from across Europe and America to Glasgow. In fact, when he moved to the University of Edinburgh in 1766, the University of Glasgow saw a significant drop in Science students—perhaps because, in the 18th century, a professor's salary depended on student attendance.

Black never married, although he was quite the gentleman of his time. He played the flute and was very popular among women—what we would now call a womaniser. He was known to frequent gentlemen’s clubs, and, occasionally, along with friends like Adam Smith and David Hume, he visited less reputable establishments near the university. He died in 1799 and is buried in Edinburgh’s famous Greyfriars Cemetery.

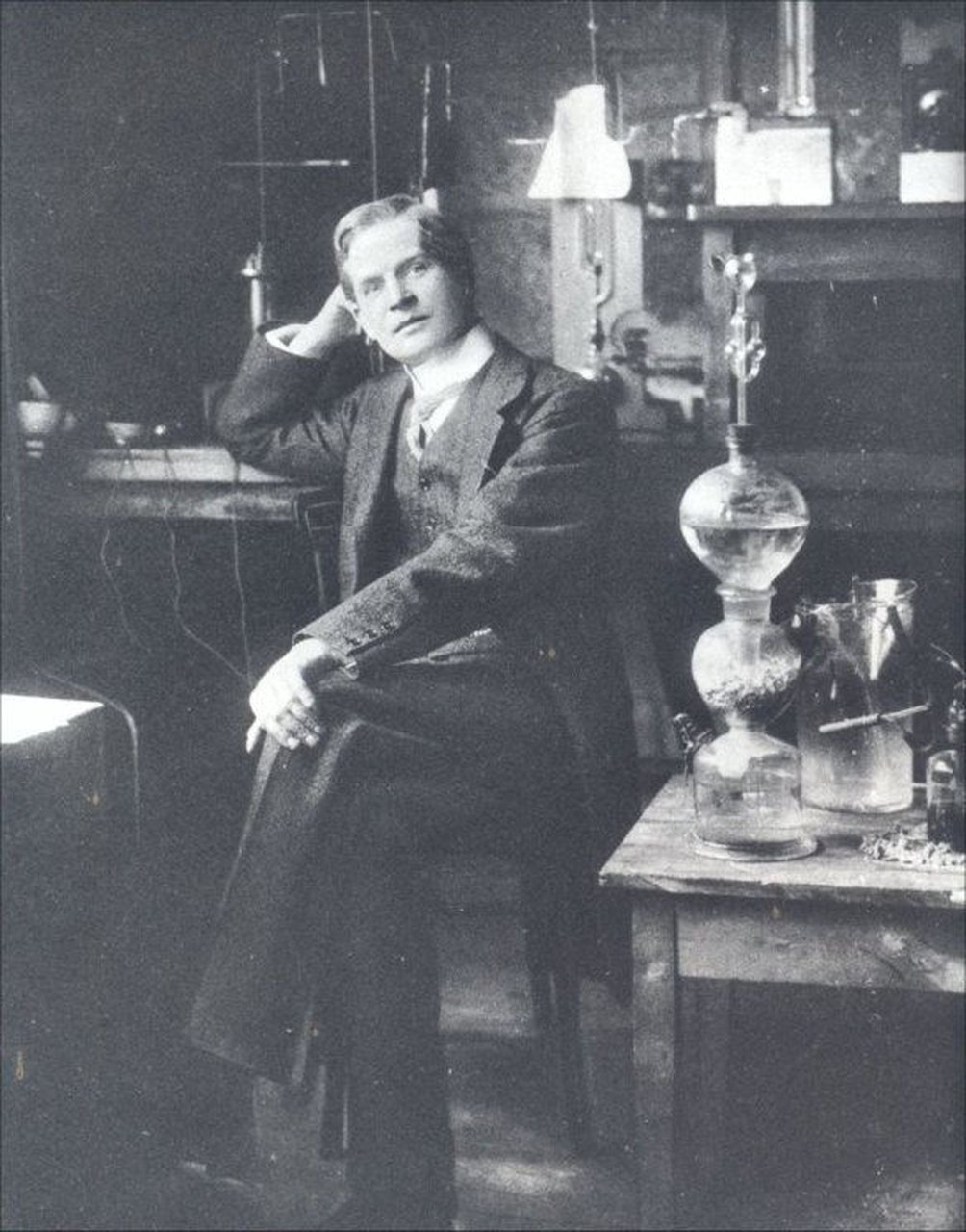

B. George Beilby's House - Frederick Soddy

11 University Gardens

55.872785, -4.290979

As indicated by the plaque beneath the window, this house is where the term "isotope" was coined for atoms of the same chemical element that have different masses, a discovery made by Frederick Soddy.

Frederick Soddy was the son of a London grain merchant, born in 1877 in Eastbourne, a small town on England’s southern coast. Soddy studied Chemistry at Oxford, though he was not particularly happy there, as scientific education at the time was somewhat chaotic. After graduating with honours, he moved to Canada to work as a demonstrator at McGill University in Montreal. There, he met the New Zealand scientist Ernest Rutherford, who introduced him to nuclear chemistry and with whom he helped discover that pure thorium released radon gas over time. From this, they deduced that some atoms were unstable and that radioactivity was the result of their decay. They proposed two radioactive series, in which uranium decayed into lead, and thorium also decayed into lead. Soddy used the word "transmutation," a term from alchemy, to describe this process.

In 1903, Soddy left Canada to work with Sir William Ramsay at University College London. One day, while walking through London, he was surprised to see radium for sale in a shop window at 8 shillings per milligram. He purchased a vial containing 20 mg of radium and studied whether it behaved like thorium. He discovered that radium emitted helium rather than radon, determining that helium was the source of alpha radiation.

Soddy struggled to work under Ramsay’s strong personality, so in 1904 he moved to Glasgow to establish his own research group. George Beilby, president of the Society of Chemical Industry, invited him to live in this house with his family. Beilby, a wealthy industrialist whose fortune came from the petroleum and ammonia industries, was very interested in Soddy’s work and its potential applications. In addition to providing accommodation, Beilby secured funding for Soddy to buy radium from Marie Curie for his experiments. Eventually, they opened a radium factory in Balloch, near Loch Lomond, taking advantage of the lake’s clean waters to separate the element for sale to pharmacists and researchers.

George Beilby was a strong advocate for women’s rights. One evening, he hosted a dinner at his house, inviting Dr Margaret Todd, who had recently published a biography of Sophia Jex-Blake, Scotland’s first female doctor. During the dinner, Soddy explained his latest discovery: he had observed that as some elements decayed, he encountered atoms with the same atomic number but different weights. These atoms occupied the same place on the periodic table despite being different. Margaret Todd then suggested the term "isotope," from the Greek for "same place."

Soddy eventually married Winifred, Beilby’s daughter. In 1918, he accepted a professorship at Oxford, where he dedicated

much of his time to improving science education at the university. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1921 and died

in 1956. His lifelong motto was:

"Beauty and truth and duty, that's all y'need to know."

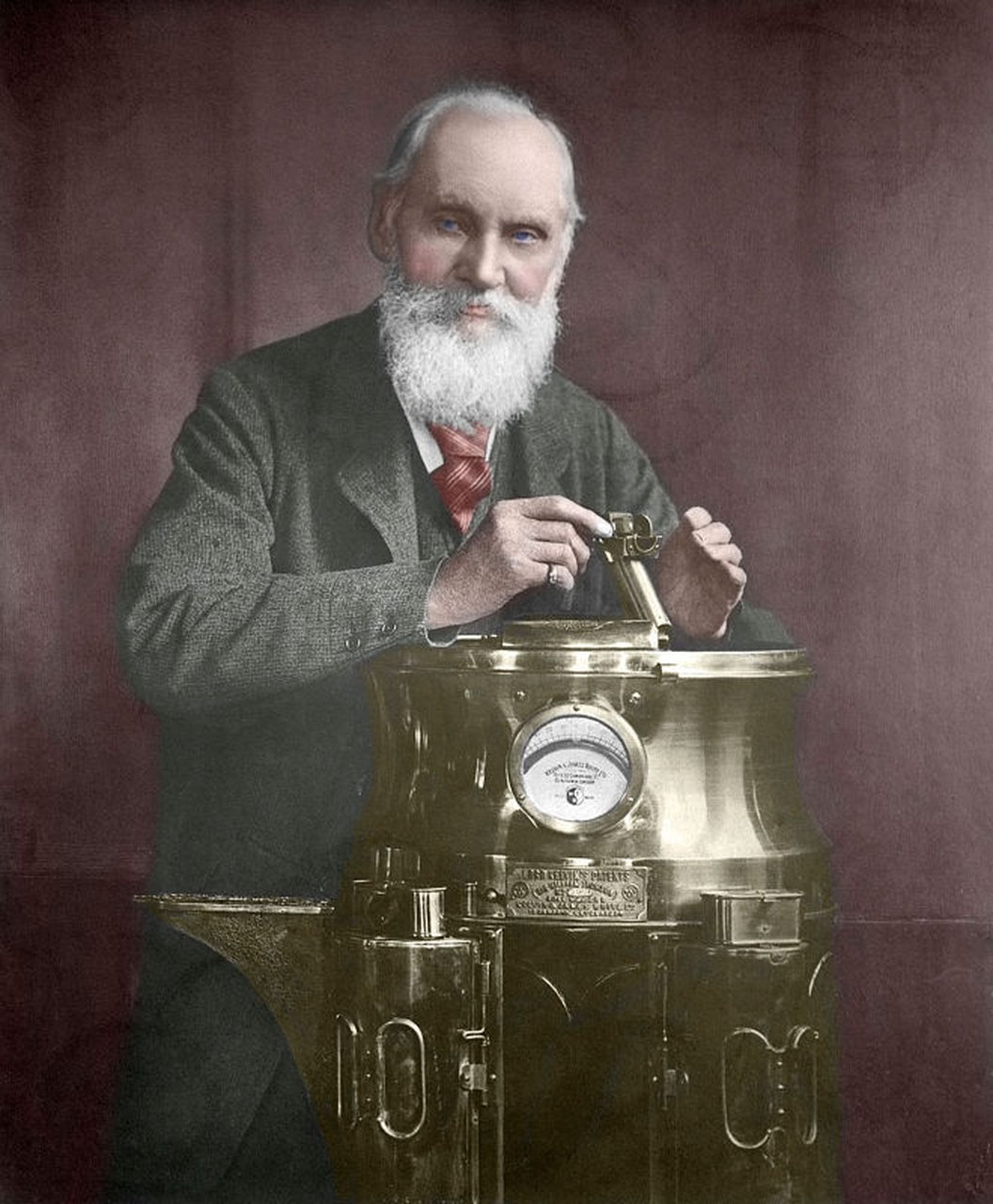

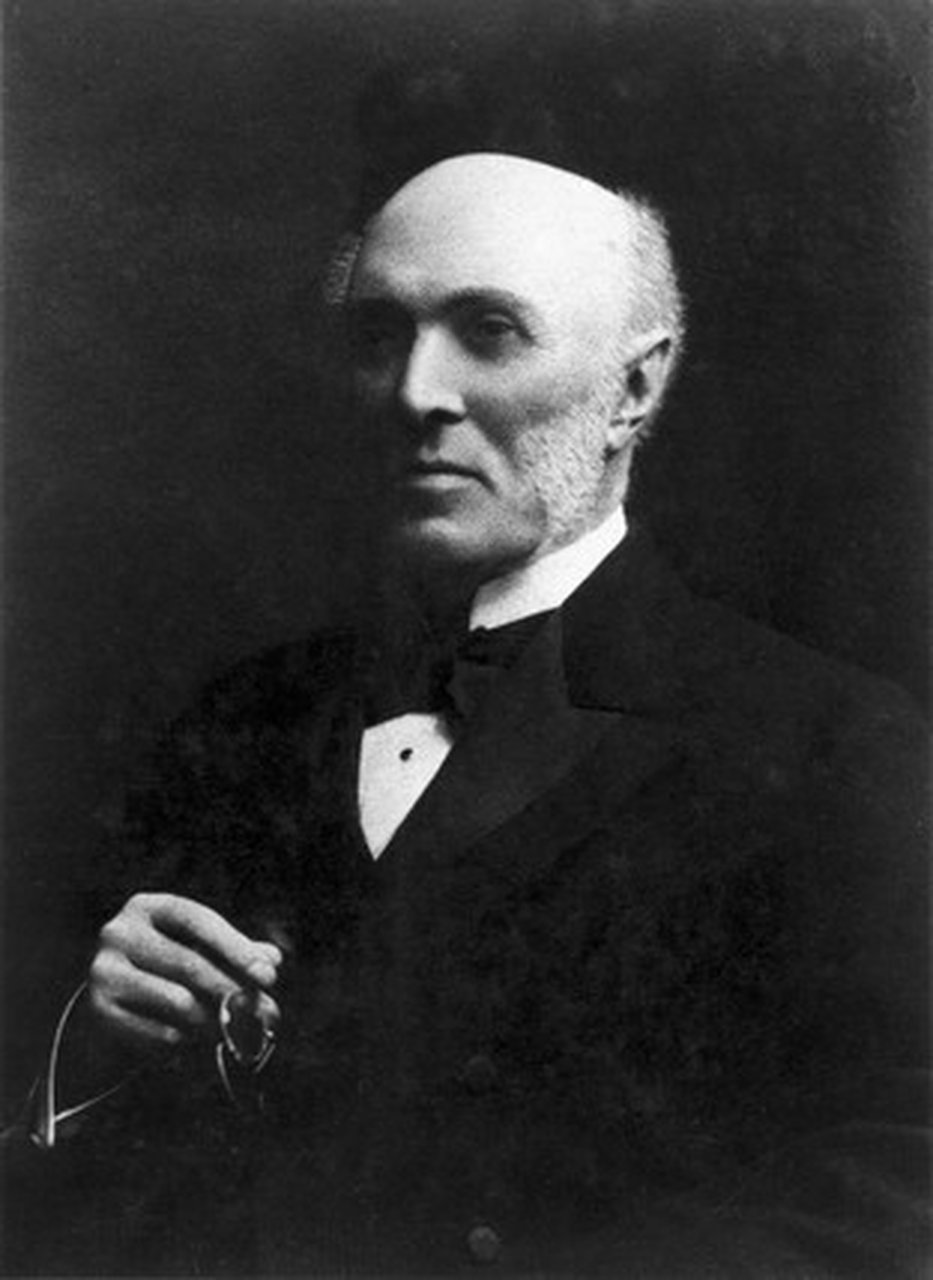

C. Lord Kelvin's House - Sir William Thomson, Lord Kelvin.

11 Professors' Square

55.871486, -4.290532

The physicist William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, lived in this house from 1870 until his retirement in 1899. It was built by the university and was one of the first houses in the world to be illuminated exclusively by electricity.

William Thomson was born in Belfast in 1824 and was the son of a mathematics professor at the Royal Institution of Belfast. In 1832, when he was eight years old, his father was appointed Professor of Mathematics at the University of Glasgow, and the family moved to Scotland. At that time, the journey from Glasgow to Belfast took almost as long as the journey from Glasgow to Edinburgh by stagecoach. The young William was what we would now consider a child prodigy, and he passed the entrance exams for university at just ten years old, becoming the youngest student ever at the University of Glasgow. His career progressed rapidly, and at only 22 years old, he secured the Chair of Natural Philosophy (Physics).

As a researcher, Thomson had a wide range of scientific interests, including thermodynamics, electricity, and magnetism, making significant discoveries in all these fields. He proposed an absolute temperature scale and made fundamental contributions to the study of mechanical energy and heat. He always sought practical applications for his discoveries and, together with an industrialist named James White, founded a company called Kelvin & White, which manufactured scientific instruments and electrical machines, making them immensely wealthy. He was responsible for the first transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866, linking Wall Street in New York with the City of London. The marine compass he invented became a standard instrument for the vast majority of large ships at the time.

In 1892, Queen Victoria granted him a peerage for his scientific contributions and his opposition to Irish Home Rule. His title, Lord Kelvin, was taken from the river that runs alongside the university and which is crossed during this tour. In 1899, he retired and moved to a mansion on the coast. He also re-enrolled as a student at the university, becoming the oldest student at the University of Glasgow. William Thomson died in 1907 and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

D. The Hunter Memorial - William and John Hunter

University Avenue

55.871985, -4.288292

This monument was designed by the Scottish architect John James Burnet and was inaugurated on 24 June 1925 to commemorate the brothers John and William Hunter.

The Hunter brothers were born in East Kilbride, south of Glasgow, in the 18th century. William, ten years older than John, also studied medicine under William Cullen, who was Joseph Black's professor. He later moved to London, where he studied obstetrics. He soon opened his own practice in the English capital, where he began researching the anatomy of pregnant women, assisted by his brother John, who helped with dissections. Over time, both brothers became two of the most successful (and wealthy) doctors in England. William was even appointed the personal physician to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III.

John also contributed to medical research, studying the growth of teeth and the role of the lymphatic system. However, he also helped perpetuate the mistaken belief that gonorrhoea and syphilis were symptoms of the same disease. It is said that this error originated when he self-inoculated gonorrhoea with an infected needle, but the patient from whom he took the sample was also syphilitic, leading John to contract both diseases.

The two brothers were avid collectors and founded their own museums—both called the Hunterian. John's collection is in London, while William's is housed at the University of Glasgow, just behind this monument. The Hunterian Collection at the university was the first museum in Scotland.

John was also somewhat eccentric and kept live animals, which is believed to have inspired Hugh Lofting to create the character of Dr Dolittle. He also served as inspiration for another famous literary figure: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Like Robert Louis Stevenson's character, his house had two doors—one for his residence and another for his collection—and his popularity, along with the envy he provoked, led to the spread of the (obviously false) rumour that he ordered murders to obtain more bodies for dissection.

William died unmarried in 1783, and his brother passed away ten years later, in 1793. John was married and had four children.

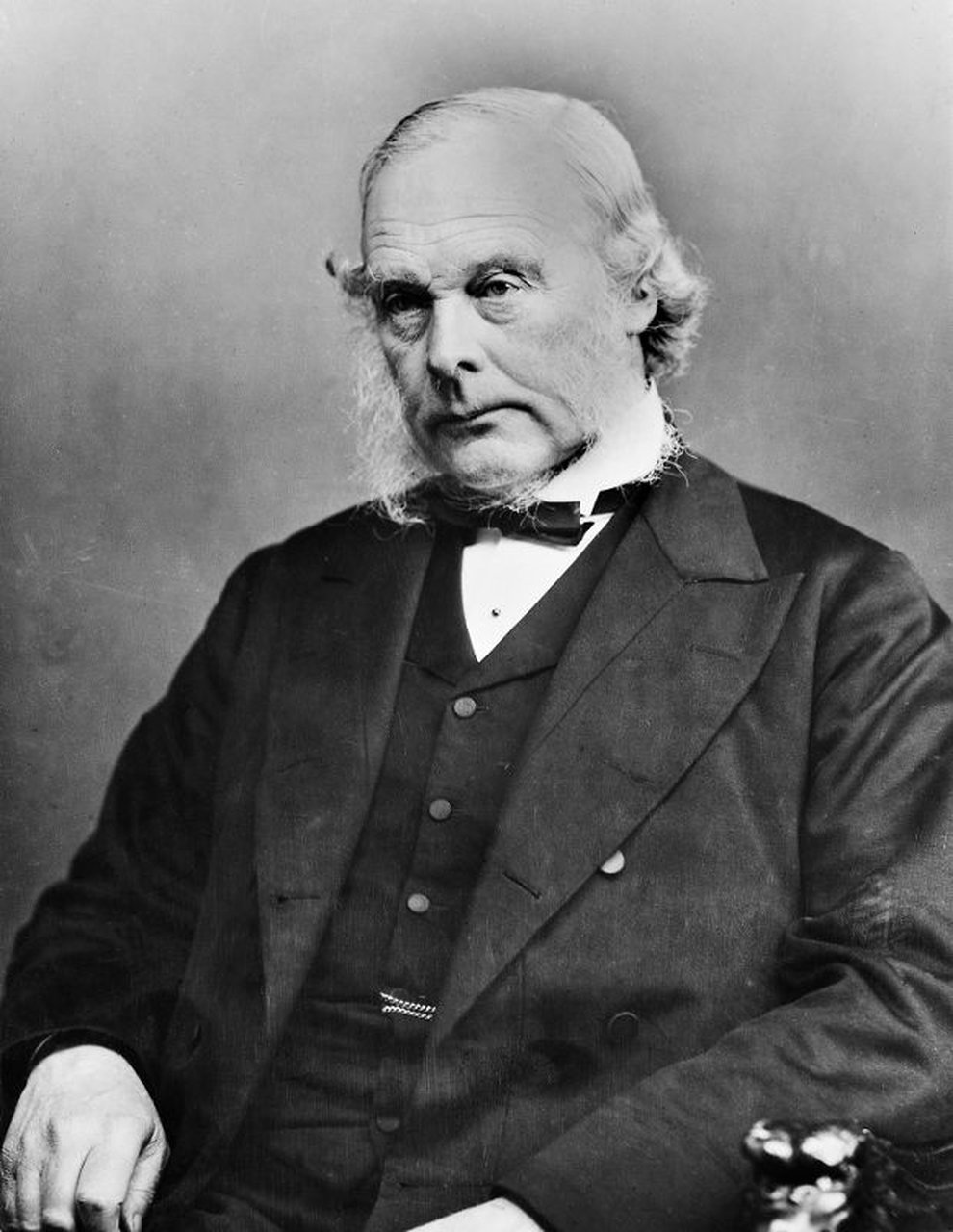

E. Lord Lister Statue - Joseph Lister

Kelvin Way

55.869465, -4.287743

Joseph Lister was born in 1827 into a Quaker family in Essex. He was an excellent student and particularly gifted with languages, speaking fluent French and German. He attended University College London, one of the few universities that admitted Quakers at the time. There, he first studied botany before moving on to medicine, which he completed in 1853. He then moved to Edinburgh, where he became the assistant to Scotland’s leading surgeon, James Syme. He eventually married Syme’s daughter, Agnes, and for their honeymoon, they spent three months touring medical institutes in France and Germany. While this may not seem particularly romantic, Agnes was deeply passionate about surgery and Lister’s work, and she remained his assistant in the operating theatre throughout his career. In 1861, Lister secured a position as a surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Glasgow and as a professor at the University of Glasgow.

It was during his years in Glasgow that he conducted most of his research. Inspired by Louis Pasteur’s germ theory—that food did not spoil if heated or treated with chemicals to kill bacteria—Lister was the first to propose that infections had a bacterial origin. Since heating a wound was not a practical solution, he began investigating which chemicals could act as disinfectants.

To understand the revolutionary impact of Lister’s work, it is important to consider the state of surgery at the time. It was widely believed that infections were caused by bad air, so hospitals were ventilated daily at noon to prevent them—ironically worsening conditions for pneumonia patients. Hygiene was not a priority for doctors, who wore the same apron for every procedure, never washing it, as the number of blood and fluid stains was seen as a badge of experience and status.

Lister experimented with various chemical disinfectants and discovered that spraying surgical instruments with a solution of carbolic acid (phenol) significantly increased patient survival rates. The same effect was observed when surgeons washed their hands and wore gloves treated with his solution before operating.

One notable case cemented Lister’s reputation: a seven-year-old boy was brought to him after being run over by an ox cart, which had crushed his leg. At the time, such severe wounds inevitably led to amputation. However, Lister applied phenol to the wounds and wrapped them in clean, disinfected bandages. Four days later, when the dressings were removed, there was no sign of infection, and six weeks later, the bones had healed perfectly.

Lister’s success led to the immediate acceptance of his antiseptic techniques. In 1869, he was appointed professor at the University of Edinburgh, and in 1881, he moved to London, where he further refined surgical procedures, including mastectomies—one of which he performed on his own sister. In 1893, Agnes passed away during a holiday in Italy, and Lister decided to retire from medicine. He died in 1912 at his country home in Kent.

Following his death, the Royal Infirmary sought to honour him with this statue, designed by George Henry Paulin. However, due to the Great War, it could not be cast and installed in Kelvingrove Park until 1924.

At this point, visitors may take a short detour to see Lister’s home in Glasgow, located at 17 Woodside Place, not far from here.

F. Stewart Memorial Fountain - Robert Stewart

Kelvin Walkway

55.867958, -4.283883

This fountain was built in 1872, with James Sellers as the architect and John Mossman as the sculptor. It was erected in honour of Robert Stewart, who served as the Provost of Glasgow—effectively the city's mayor—between 1851 and 1854. He was a pioneer of public health and, during his tenure, successfully oversaw the construction of a canal to bring fresh water from Loch Katrine to Glasgow to combat waterborne diseases, primarily typhus and cholera. The project was completed in 1859, and its effectiveness was swiftly demonstrated during the great British cholera and typhus epidemic of 1866, during which only 55 people died in Glasgow. In contrast, during the 1832 epidemic, over 4,000 people perished, despite Glasgow having only half its later population.

The fountain, built in 1872, is made of granite and sandstone and is adorned with a bronze figure of the Lady of the Lake, the protagonist of a poem by Sir Walter Scott. At the base, one can see a bust of Stewart, alongside the coats of arms of Glasgow and Scotland. Other decorations include zodiac symbols and depictions of the wildlife native to the Trossachs region, where Loch Katrine is located. The fountain was restored in 2009 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Stewart’s pioneering project.

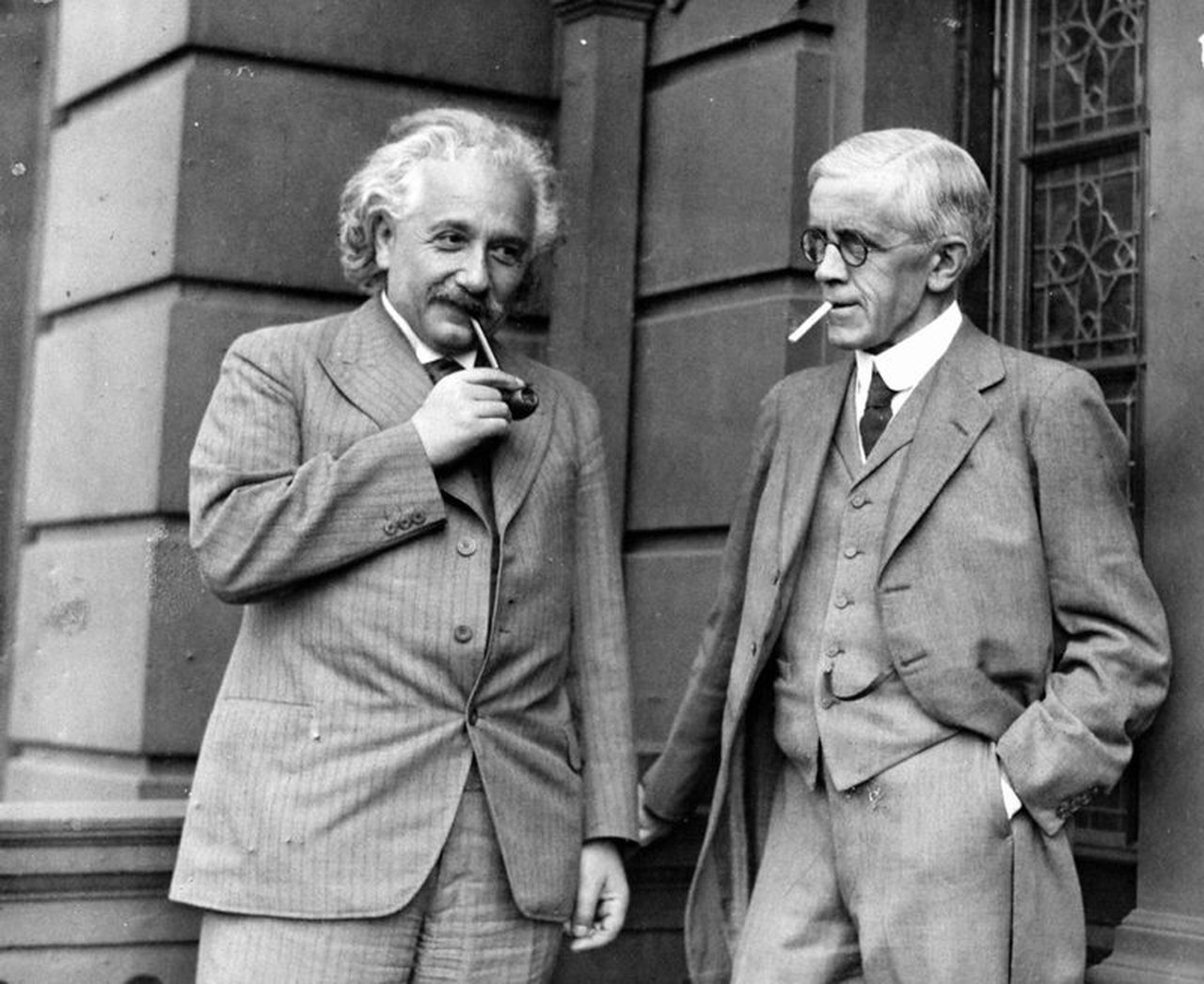

G. Casa de Archibald Young - Albert Einstein

5, Park Gardens

55.867789, -4.280096

This is the house of Archibald Young, who was the Regius Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow from 1924 to 1939. Archibald had served as a surgeon during the Second Boer War and the First World War, during which he revolutionised the treatment of gunshot wounds. However, his specialities were neurosurgery and pain management.

The reason this tour stops at his house is the curious fact that, besides being a great surgeon, Young was responsible for hosting Marie Curie and Albert Einstein during their visits to Glasgow. It was at the entrance of this house that the famous photograph of Einstein smoking his pipe was taken—Mrs Young did not allow smoking inside. Einstein visited Glasgow in June 1933, where he received an honorary doctorate from the university and took refuge from the instability caused by Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany. He also delivered the Gibson Lecture in the Bute Hall of the university, speaking about the theory of relativity and the history of his scientific work.

H. Free Church College - John Kerr

30 Lynedoch Street

55.868319, -4.276509

All the towers visible in this area belong to the buildings of the Free Church of Scotland College. The structure with three towers—two twin neo-Romanesque ones and a campanile—was designed by Charles Wilson in 1857 and housed the classrooms. The fourth tower—a perpendicular Gothic-style structure—belonged to Park Church, the campus church built at the same time but partially demolished in 1968.

The most notable professor at this college was Reverend John Kerr. Born in 1824 in Ardrossan, the son of a fishing boat builder, Kerr enrolled as a theology student at the University of Glasgow in 1841. During his final years of study, he also took some science courses, becoming close friends with the professor William Thomson, who was six months older than him. After completing his studies, Kerr was ordained as a minister, though he rarely practised. Instead, he began teaching mathematics and physics at the Free Church of Scotland’s teacher training school housed in this building, while continuing to collaborate with his friend—who would later become Lord Kelvin—on new experiments.

It was here, in the college’s laboratory, that in 1875 Kerr discovered that applying an electric field to a material made it birefringent—meaning that a beam of light could be controlled using an electrical circuit. This discovery—long sought by Faraday without success—enabled modern technologies such as television and fibre-optic communication, among others.

Kerr was also one of the most fervent advocates of the metric system in the British Empire, although, as daily life demonstrates, he was not particularly successful in this endeavour.

John Kerr and Lord Kelvin remained lifelong friends—quite literally, as both passed away in 1907, just four months apart. John Kerr is buried in the Glasgow Necropolis alongside his wife.

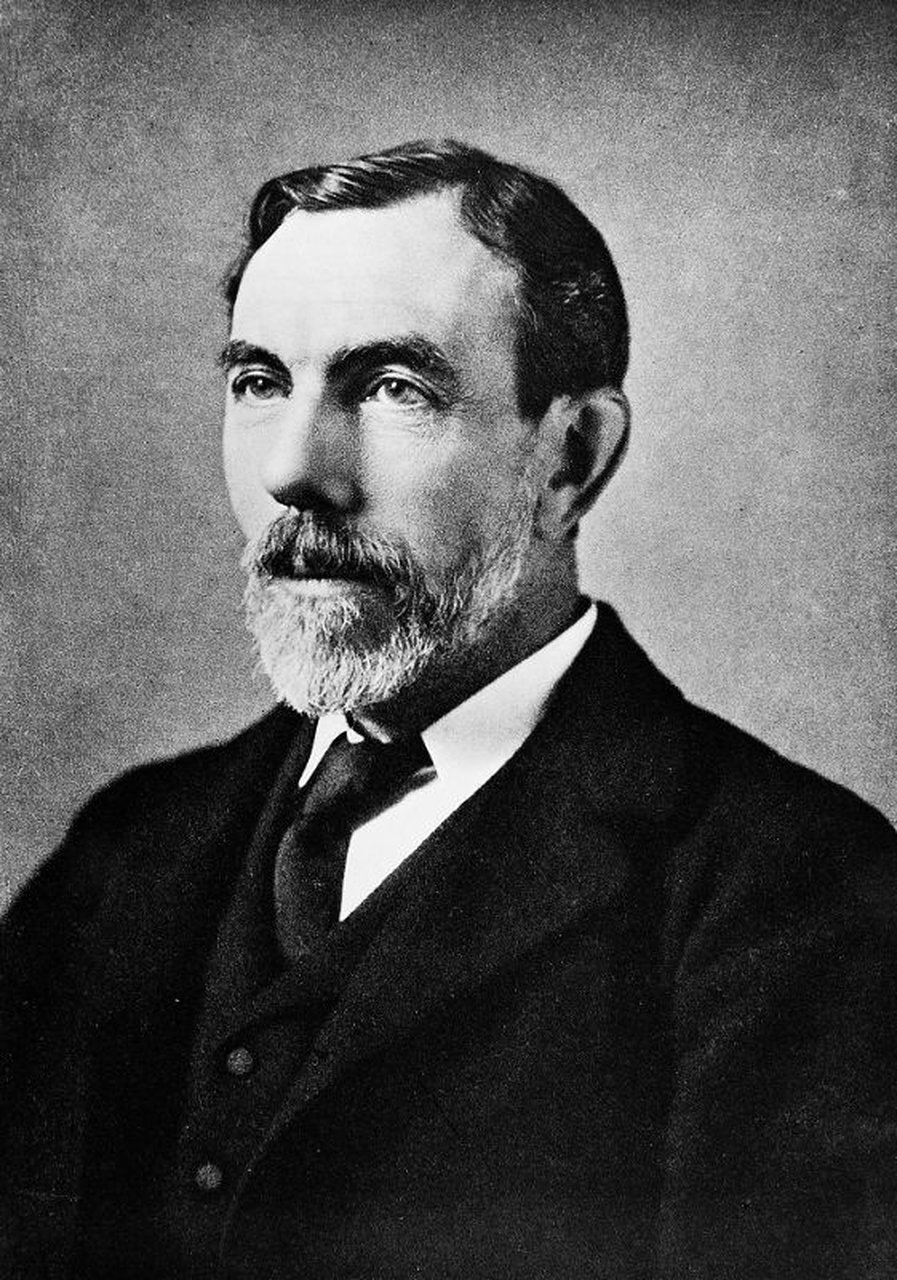

I. Birthplace of William Ramsay - William Ramsey

2 Queen Crescent

55.870576, -4.270295

William Ramsay was born in this house in 1852. He was the son of a civil engineer, and thanks to his family's comfortable position, he was educated at Glasgow Academy, one of the city’s most elite schools. Located by the River Kelvin in Kelvinbridge, it had that Harry Potter-esque atmosphere, with four houses competing against each other. From an early age, Ramsay wanted to be a chemist, and as soon as he finished school, he enrolled at the University of Glasgow to pursue his dream. Additionally, to gain more experience, he spent his afternoons apprenticing in the analytical laboratory of Robert Tatlock, located on George Street, roughly where the University of Strathclyde stands today. Ramsay had a remarkable talent for conducting experiments and a great deal of self-confidence. Halfway through his studies, he left university and moved to Heidelberg, Germany, hoping to become a student of the most renowned chemist of the time, Robert Bunsen—famous for inventing the Bunsen burner. After six months of trying, he did not succeed, and in the end, he completed his thesis under Wilhelm Rudolph Fittig at the University of Tübingen. In 1872, having earned his doctorate, he returned to Glasgow and began working first as a lecturer at Anderson College—the precursor to today’s University of Strathclyde—and later at the University of Glasgow, where he researched the volume occupied by different compounds at their boiling points. This work would provide him with exceptional skills in handling gases, which would later prove invaluable for his discoveries.

In 1880, he moved to Bristol, and in 1887, he relocated to London. One day, while attending a seminar by physicist William Strutt, better known as Lord Rayleigh, he heard that synthetic nitrogen was lighter than nitrogen extracted from the atmosphere. Ramsay hypothesised that atmospheric nitrogen must be contaminated with a heavier gas and set to work trying to isolate it. Six months later, he wrote a letter to Rayleigh informing him that he had successfully isolated a new gas from atmospheric nitrogen, which appeared to be completely inert. He named it argon, derived from the Greek word for ‘lazy.’ Following this discovery, he continued his experiments and soon identified other gases in the air: neon, krypton, and xenon. He also became the first to characterise helium, a gas previously known only to exist in the Sun, as inferred from its spectral lines. For these discoveries, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1904.

After receiving the Nobel Prize, he focused mainly on collecting awards, teaching, and earning money by advising companies. It was through this consultancy work that he suffered his greatest scientific failure. A company paid him a substantial sum to endorse a method for extracting gold from seawater. The confidence inspired by Ramsay’s approval led many people to invest in the company, which began purchasing coastal land for its factories. However, it was eventually revealed that the system was a pyramid scheme. Following this scandal, Ramsay returned to research, and together with Frederick Soddy, he detected helium in radium emissions. Of all the noble gases in the periodic table, the only one he did not discover was radon, though he spent a great deal of time studying it. It is possible that exposure to the radioactivity of this gas contributed to the nasal cancer that ultimately claimed his life in 1916.

|

Next post: 9 Mar 2018: Best Poster Prize at the RSCPoster Twitter Conference |

Previous post: Advertising Marathon 2017 |