Detection of cosmic particles with a fish tank

A cheap fish tank from a bazaar, black packing tape, a piece of black felt, a flashlight, a bag of water, dry ice, a metal plate the same size as the fish tank, glue, and a cork box. That’s all you need to build a homemade cosmic particle detector.

Cosmic particles have a very pompous name, but they are nothing more than atomic nuclei and other subatomic particles such as electrons or muons that originate from nuclear reactions happening throughout the universe. Most of them collide with atoms in the atmosphere, generating a new series of lower-energy particles that reach the Earth’s surface. Thanks to this, life on Earth can exist, because we must not forget that these particles constitute what we call “radioactivity” and if it weren’t for the atmosphere and Earth’s magnetic field, our cells—and their precious genetic material—would be thoroughly scorched.

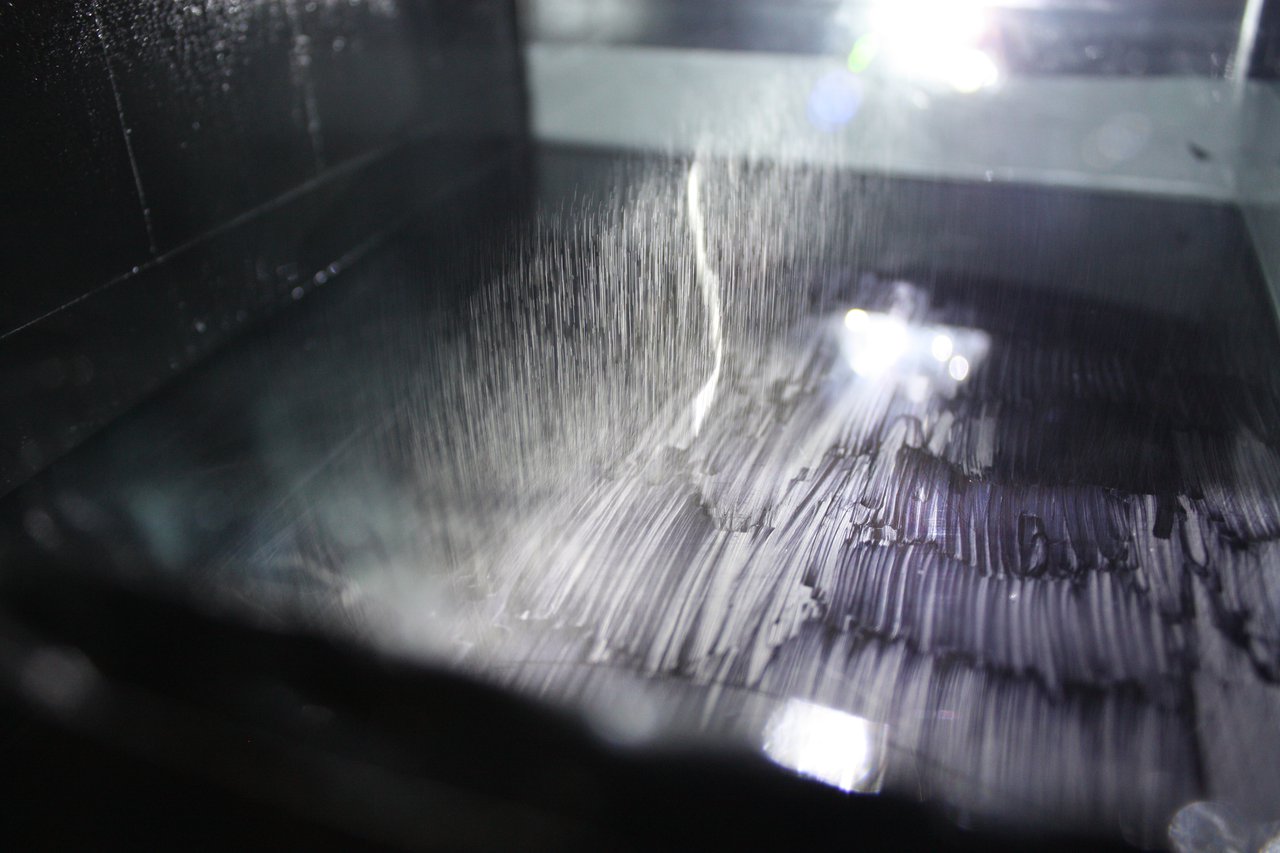

The experiment I present here is nothing more than the homemade construction of a cloud chamber. These chambers have been devices used for more than a hundred years, initially for the study of cloud formation and later, after observing track formation, for the study of ionizing radiation. Their operation is simple: they create an atmosphere of supersaturated vapor (which under the given conditions should have already condensed, but due to the way those conditions were achieved, it has not yet done so). In this state, the vapor molecules are on the verge of joining together and condensing, but they do not because they must overcome the surface tension created when a droplet forms. In these conditions, the appearance of a cosmic particle with electric charge provides the small push the molecules need to condense. The cosmic particle ionizes molecules as it passes through the mist, and the charged molecules created attract each other like magnets, forming larger molecular aggregates and the subsequent condensation of the group. To the observer, what appears is a sudden trail of condensed droplets showing the path the particle followed through the vapor.

To prepare supersaturated vapor, you can use water, alcohol, chloroform… [1] In the video we used isopropyl alcohol because

its evaporation temperature is ideal and it ionizes very well, but if you use 96% ethyl alcohol (the kind sold everywhere),

the experiment works just as well.

You also need a sealed enclosure. That’s where the fish tank comes into play. It must be cleaned very thoroughly, and at

its base, a piece of felt is glued with superglue (any glue based on cyanoacrylate works, the important thing is that it resists alcohol or water). Once the glue dries,

soak the felt well with alcohol (in the video experiment, 20 ml was enough), cover the fish tank with a thin metal plate

(it’s important that it’s metal so heat can transfer well), and seal it tightly with electrical tape.

Creating the greatest possible contrast makes it much easier to observe the tracks. That’s why the experiment is done in

a dark room with lateral lighting from a flashlight. Black felt is also used, the metal plate is painted black, and the

sides of the fish tank serving as background are covered with black tape.

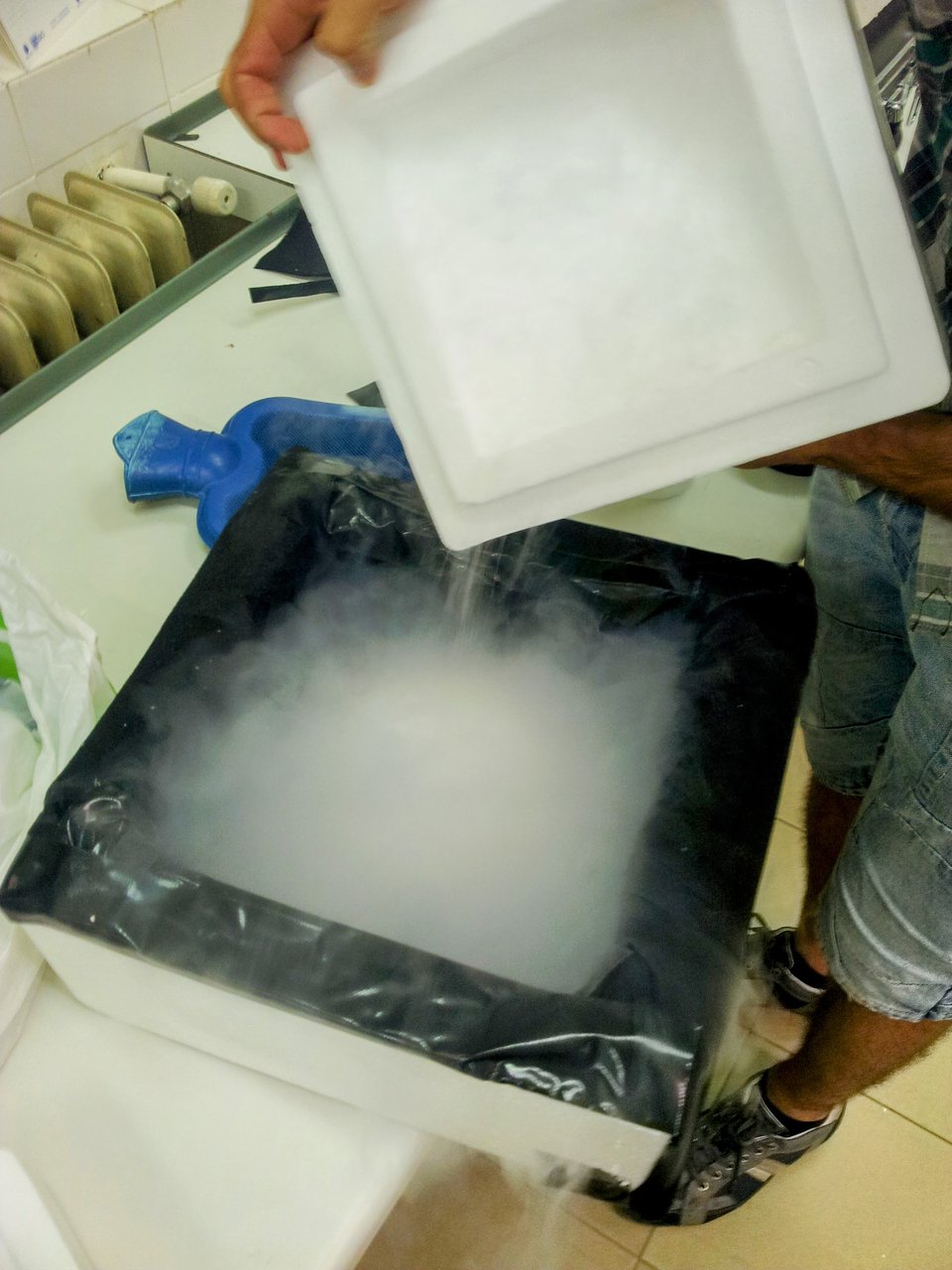

Once everything is ready, all that remains is to apply a very large temperature difference to the chamber. On the side with the felt, heat is applied so the alcohol evaporates, and on the side with the metal plate, cold is applied so it condenses. The temperature difference must be very large, from about 80 ºC to -80 ºC, so that at an intermediate point, the right conditions are achieved to obtain the supersaturated alcohol vapor necessary to observe the particles. To achieve that very cold temperature, place the fish tank upside down with the metal plate resting on dry ice inside a white cork box (expanded polystyrene, which is called differently in each English-speaking country). The box can also be lined in black to improve observation.

Dry ice (CO2 in solid state) is not hard to find; it’s sold by gas distributors such as Air Liquide. The only drawback is that the minimum amount they sell is 10 kg for about €30, so if someone who works regularly with it can get you a small amount, much better (no more than 200 g is needed).

To keep the top of the chamber at about 80 ºC we used a device that has been a bedroom companion of Spaniards for decades:

Once everything is set up, all you have to do is wait for the chamber to stabilize. After about five minutes, a wavy mist appears at the base of the chamber. Gradually this mist grows, and the first tracks begin to appear above it. A rain of tiny droplets from the condensing alcohol also begins to fall. At that point, the optimal conditions for observing cosmic particles have been reached. Let the show begin!

[1] The Principles of Cloud-Chamber Technique, J. G. Wilson, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1951.

|

Next post: Dance of starlings over the Tormes River |

Previous post: The Origin of the Autonomous Community of Castile and León (Part III) |